If you wanted to be generous, you could separate the era of Chelsea since the takeover by Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital into three distinct phases.

The first was the “Summer and Winter of Todd,” the period in 2022 and early 2023 when Boehly was basically — and later officially — the club’s sporting director. If there was a semi-available, semi-famous player out there or someone who was linked with a transfer to another big club, Chelsea tried to sign them.

This led to the arrivals of players like Raheem Sterling, Kalidou Koulibaly, Mykhailo Mudryk, and Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang. It almost led to the signing of 37-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo. And despite spending €630 million on transfer fees across both windows, the team finished in the bottom half of the Premier League table.

The next phase, in the summer of 2023: same thing, but young guys. This led to a bunch of misses, over €400 million in fees spent, but even the best clubs whiff on transfers. The average hit rate is only about 50% — transfers are hard. More importantly, though, it was during this period that Chelsea acquired a pair of 21-year-olds who would become the team’s two core superstars: Cole Palmer and Moisés Caicedo. The club finished sixth in the following Premier League season.

And then came last summer, when Chelsea signed a ton of young-ish players with top-league experience. None of these deals were what you would call “good values” — see: João Félix and Kiernan Dewsbury-Hall.

But they built out the options beyond Palmer and Caicedo and essentially allowed the club to play two completely different teams in the UEFA Conference League and the Premier League. They won the Conference League and finished fourth in the Premier League — closer to second-place Arsenal than Arsenal were to first-place Liverpool.

Coming into this summer, you had a young team that was back in the Champions League. They had more league-average-or-better depth than perhaps any club ever has. And they had two true genuine stars in Palmer and Caicedo, who were just about to enter their primes.

While it seemed like Chelsea were a hedge fund posing as a soccer club for the past three years — acquiring any player who they thought provided a “transfer value” regardless of how he fit on the roster — they were suddenly in a position to try to start winning major trophies. They could start redirecting the billion-plus in transfer fees on a couple more stars to compliment Caicedo and Palmer.

Or … not. Instead, based on Chelsea’s business so far this summer, we find ourselves stuck in a familiar place: No one has any idea what they’re doing.

Why none of Chelsea’s new signings move the needle

In a vacuum, almost everything Chelsea have done so far this summer is defensible.

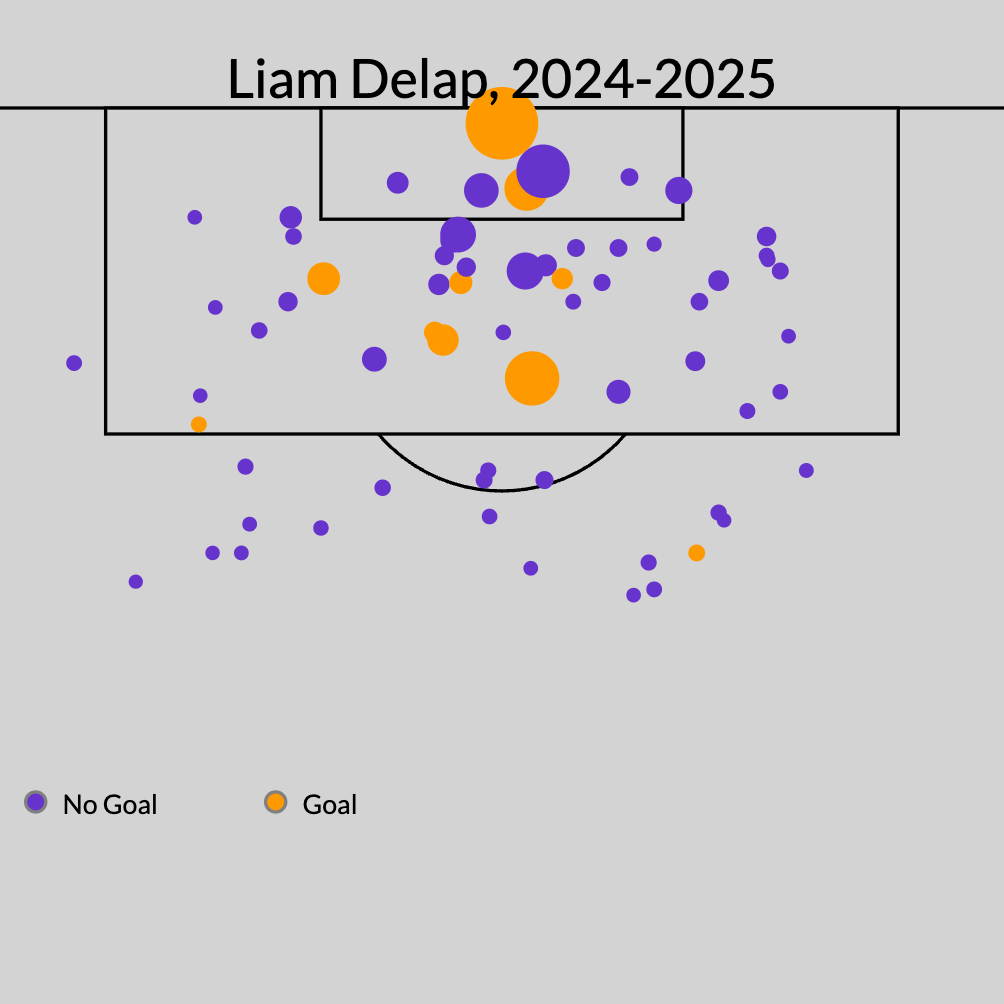

First, they spent €35.5 million to acquire 22-year-old striker Liam Delap from relegated Ipswich Town. Delap scored 10 non-penalty goals and added two assists for one of the worst teams in the league. He overperformed his expected-goals number of 7.8 by a good deal, which suggests unsustainable output:

And beyond some ball-carrying skills, he didn’t really add much else in attack. But Delap is still quite young, and plays one of the most expensive positions in the sport. He’s a good athlete and at least profiles as the kind of player who could suddenly improve by an exponential amount, as his game intelligence and technical skills improve.

While teams frequently overpay for what they imagine a player could do one day, as opposed to what they already know he can do, Chelsea weren’t doing that here. Worst case, they’d be able to move Delap on in a year or two and make back what they spent.

Then came João Pedro, who is a Roberto Firmino-shaped player who is not yet anywhere near as good as Firmino. The 23-year-old Brazil international is a fantastic presser who is great at finding space between the lines, but unlike Firmino, he hasn’t produced too many goals or assists.

Over two years with Brighton, Pedro averaged 0.43 non-penalty goals plus assists per 90 minutes — with just slightly better underlying numbers. Normally, you’d think this is the kind of player who’d be undervalued by the market — someone with hidden, softer skills worth taking a risk on — but the five penalties he scored this past season changed all that. Chelsea paid €63.7 million, or Champions League-starter-level money, for a player who has to improve a good deal to get to that level.

Lastly, Jamie Gittens would’ve fallen into the same bucket as Delap. He’s 20 and another fantastic athlete. As a right-footed left winger, he’s also playing one of the most in-demand positions in the sport. It’s just that he’s … not all that good yet.

In two years at Borussia Dortmund, he averaged 0.38 non-penalty expected goals and assists — or slightly worse than what Joshua Zirkzee put up for Manchester United last season. And this is all in the Bundesliga, a league that historically boosts the production of attacking players.

Put another way: your production doesn’t improve when you move from Germany to England. Gittens is an intriguing prospect but Chelsea paid (€64.3 million) like he was a Champions League-quality starter.

None of these players raise Chelsea’s ceiling, while their floor was already quite high because of all the depth they’ve built up over the past year. If you were trying to project Chelsea’s title and Champions League odds, none of these signings — even when you add them all together — would change anything.

On top of all this, it seems like Chelsea might be ready to move on from right winger Noni Madueke, who has, according to reports, already agreed to personal terms with Arsenal.

1:18

Nicol: Madueke to Arsenal makes no sense

ESPN’s Steve Nicol believes Noni Madueke’s potential move to Arsenal from Chelsea doesn’t “make sense.”

Madueke is one of the few success stories of the Boehly-Clearlake model — acquired for €35 million as a 20-year-old at PSV, he was one of Chelsea’s most-used players last season. And his underlying numbers — 0.61 expected goals and assists, versus 0.44 goals and assists — suggest he might be even better next season. He slows down play a bit too often for my liking, but he’s the exact kind of player who could explode: his underlying numbers improve and his production catches up to the quality of shots he’s taking and creating.

Why would you move on a 23-year-old like this? And why would you let him go to a direct competitor?

So, what is Chelsea’s plan?

The new owners at Chelsea have come up with two legitimate innovations.

The first was to exploit the way transfers are accounted for in financial regulations. Since amortization allows you to divide the transfer fee across the years of a player’s contract, Chelsea’s seven-year contracts have allowed them to spend more money on transfers than any team ever has without suffering much punishment from soccer’s governing bodies.

While there is reason to remain skeptical of the competitive benefits of this approach — they gave Palmer a new contract after one season, thus negating any “value” gained by locking him into a long-term deal below his market rate — it was undoubtedly a new approach.

The second innovation comes with their other club, Strasbourg, in Ligue 1. Chelsea have legitimately created their own feeder team, in a competitive league, where they can control the tactical, training, and developmental environment for all the players. This allows them to carry a bigger roster of players. It gives them a place to stash players who don’t currently fit in the first team. And, really, it just gives them more bites at the apple. A second team of players means that Chelsea simply have more who could conceivably turn into stars — and they’re able to give them all more playing time.

But to what end? What is the actual point of this enterprise?

Unlike under former owner Roman Abramovich, the interests of Chelsea’s owners are not directly aligned with the fans. As a Russian oligarch, Abramovich had his own personal interests, which meant he didn’t care about anything other than Chelsea winning games.

“It’s not about making money,” Abramovich told the BBC in 2003, after purchasing Chelsea. “I have many much less risky ways of making money than this. I don’t want to throw my money away, but it’s really about having fun and that means success and trophies.”

This is all that most fans care about, too. He spent billions of dollars of his own money, and the team won lots of trophies.

Boehly and Clearlake have spent nearly $2 billion in transfer fees thus far, but these are not sugar-daddy owners, and they’re not in the business of sports-washing, either. Boehly’s initial spending spree did kind of feel like exactly what a rich guy would do with this newfound power — Man, wouldn’t it be cool if I got to sign Cristiano Ronaldo? — but that’s not why he’s part of this ownership group. And Clearlake, the majority owners, are a private-equity fund that manages some $75 billion in assets. A private-equity fund doesn’t buy a soccer team with any goal other than making a profit.

But Chelsea’s financial engineering of contracts doesn’t help with that. It’s just accounting. All it does is help them not run too far afoul of UEFA and Premier League spending regulations. (They were recently fined $36.5 million by UEFA for breaking spending rules.) It doesn’t change the fact that they’ve spent €1.62 billion on transfer fees since the summer of 2022. And even when you account for all of their player exits over that period, they’re still more than €1 billion in the red.

Now, every new club owner thinks they can juice out more profits by raising ticket prices, building a new stand, creating an All-Star game, whatever. Americans, in particular, all talk about these minor levers after they buy their clubs. But in soccer, player wages take up a much bigger percentage of team revenues than they do in the collectively-bargained American sports. Nearly two-thirds of revenue goes to wages in the Premier League on average, while it’s only slightly above or even below 50% in the major American sports. As things stand in the soccer world, you have to spend most of your money in order to win.

And if Chelsea don’t win, this is a failure. Obviously, it’s a failure — that’s the whole point. But more specifically, these guys paid more than $5 billion to buy Chelsea. And the true value in owning a sports team comes from the increased valuation of the team over time. For pretty much the entire modern era, sports teams have appreciated at a consistent rate. But unlike in the cartelized American sports that have drafts, no relegation and various parity-inducing mechanisms, the value of a soccer team has a relatively large correlation with winning lots of soccer games, raking in the prize money that comes with it, increasing your fanbase, and raising your profile.

Now, it’s hard to believe that the people running Chelsea don’t know most of this. But it’s equally hard to understand what it is they actually think they’re doing. The new owners have spent a ton of money on this team, but not with a clear vision to improve results — remember, this team finished third in 2021-22. Their performance hasn’t come close to their overall outlay. Given where things currently stand, it’s a struggle to see how this club is now worth more than the $5 billion the owners paid to acquire it.

Despite all of the incredible inefficiency of the past three years, though, the club really did seem like it had reached a point where they were ready to shift into a new gear and try to ascend to a new level of competitiveness. Instead, this current summer suggests just more of the same: Chelsea’s owners view their roster as a balance sheet, a list of names with multi-million-dollar valuations attached to them. Every potential transfer is another deal to be won.

After all, it’s a lot easier to focus on that and ignore the hard part: figuring out how to win more games.